MAGAZINE: SOUTHERN LIVING, HINGE INQUIRER PUBLICATIONS

SUBMITTED DATE: NOVEMBER 2014

(Original Submission)

GO NATIVE

A little girl heeds her grandmother’s instruction and gathers abaca and pineapple threads. She watches her mother prepare herbs and tree barks to dye the fibers in iridescent hues. These are the same strands they use to thread the loom. She sits quietly beside her grandmother who’s working the loom, displaying the intricacy of the warps and wefts. It will take hours, sometimes even days, before the weave reveals the elaborate patterns that echo nature and spirituality. Even at her youth, she understands the craft and pride that exist with the chore. And she, along with many indigenous weavers speckled across the country, share a common legacy that was once considered as strong as currency and a symbol of stature.

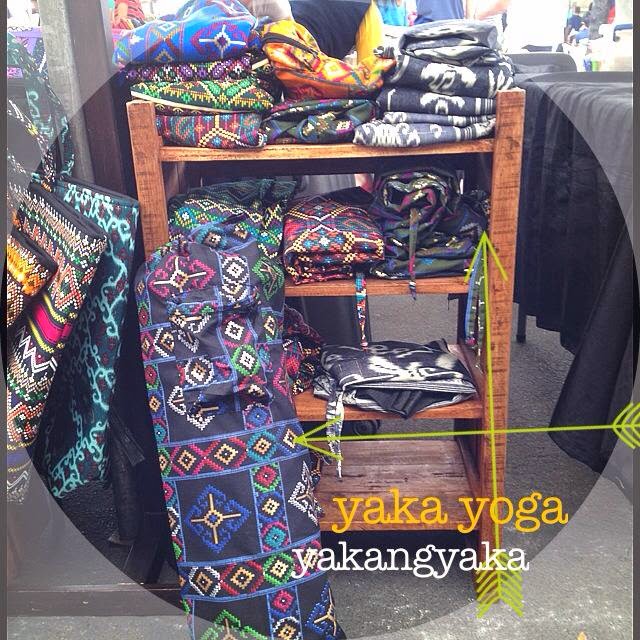

This is the heritage Kelly Murga Mortensen of Yakang Yaka has been exposed to. Yakang Yaka, which translates to kayang-kaya or ‘never give up,’ is a local business currently available in the Legazpi Market that buys and sells handmade Philippine crafts, such as weaved items and accessories, with the purpose of giving back to the local communities. Growing up in Zamboanga, Kelly’s respect for the ethnic groups and their crafts is an innate perception.

Kelly’s heart always belonged to her hometown despite having to live in another country. She and her family frequented Zamboanga every summer and, as a child, she witnessed her family support native villages in the city. Zamboanga and its neighboring towns were not spared from the repercussions of civil conflict. Such strife bleared its noble repute – the center of barter trading, the capital of the former Moro province, and “Asia’s Latin City.” Prominent families migrated out; including Kelly’s when desperation crept after her brother was kidnapped. The native groups and their livelihoods were affected. Most were forced to leave their villages, pursue domestic jobs, and often abandon their customs. The art of weaving slowly faced demise.

It may be the philanthropic trait ingrained in Kelly that made her grasp the potential of the ethnic weave and the necessity to empower the native groups. “Every time I went back home to visit, I see the desperation. After the war it just got to the point where I was frustrated because I knew that there were a lot of groups that were displaced. I knew that I wanted to help out,” she says. With the support of her family and friends, indigenous weavers, along with designer friends involved in creating contemporary designs, Kelly established Yakang Yaka as a way to revive the dying art, turning it into modern pieces such as shoes or bags that people can proudly wear.

Kelly adds, “I want to make indigenous cool again. Why are we buying Forever 21? We're buying Native American patterns that are made in China. Why is it preventing us from thinking that this is cool?” If we intend to bolster the local economy and improve the lives of our ethnic brothers, these are just some of the hard questions we must acknowledge.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Search This Blog

Copyright © • SAMANTHA RAMOS-ZARAGOZA • All Rights Reserved

Blog at Blogger.com • Template Galauness by Iksandi Lojaya

Blog at Blogger.com • Template Galauness by Iksandi Lojaya